HISTORY

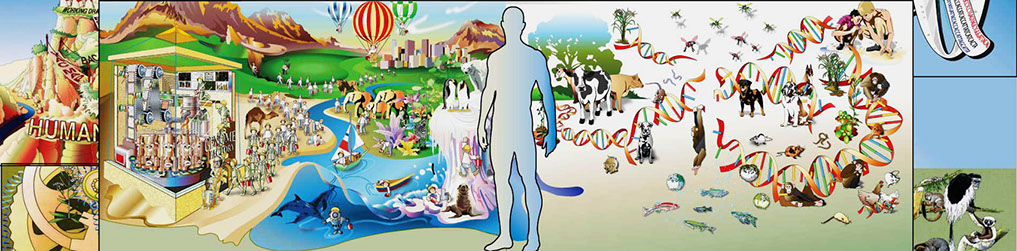

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was a 13-year research project carried out in more than 20 laboratories around the world. The goal of the HGP was to discover all 20,000 to 25,000 human genes, determine the sequence of the 3 billion DNA subunits contained in the human chromosomes or "genome," and make this information available for further study. The HGP has contributed to improving human health by enabling a better understanding of the molecular basis of various diseases.

The idea of sequencing the entire human genome faced heavy criticism and opposition upon its conception in the mid-1980s. Many scientists worried it was an unreachable goal whose exorbitant costs would crowd out funding to other crucial research. With encouragement from legendary scientists like Renato Dulbecco, however, a large-scale sequencing project gradually gained support.

Initiated as a joint project of the U.S. Department of Energy and U.S. National Institutes of Health, the HGP grew to become an international consortium of dedicated researchers in the United States, United Kingdom, France, Germany, China, and Japan.

Getting the HGP started was not easy, but the consortium proved the project’s worth by achieving amazing success more than two years ahead of schedule.

Sequencing the 3 billion base pairs of the human genome—one of the major achievements of modern science—has provided a foundation for much of the biology that followed and has already produced significant research results. The primary research materials of this unusual project—both in its scale and novelty of research, as well as in the level of international cooperation—need to be preserved.

Because it was such a large project, distributed over labs in six countries, and because it spanned the time before and after widespread use of the World Wide Web (1990-2003), the HGP presents a challenging topic for scholarly research.

The Human Genome Project is immensely important to historians and other researchers. The documentation related to this watershed project, however, lay scattered in disparate institutions and archives around the world.

It is our goal to document this monumental success story.

ABOUT OUR PROJECT

Initiated in 2009 by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and The Wellcome Trust, The International Catalog of the History of the Human Genome Project represents the first step in providing that critical documentation.

This descriptive catalog of the papers and other materials held by scientists and institutions of the International Consortium will guide historians to the materials that are now spread across institutions, laboratories, and libraries throughout the world. Specifically the Catalog will:

• identify and prioritize Human Genome Project primary materials worldwide, including accounts of major meetings, lab notes, letters and e-mails, photos, videos of oral history interviews, digital documents, landmark papers, legal proceedings, and grant applications

• create a system to organize these materials

• make these materials publicly accessible.

This project was explored and discussed further in a series of meetings on the need to preserve the HGP’s legacy:

• June 2009 at the Banbury Center, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

• May 2012 in the Banbury Center, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

• June 2014 in the Carnegie Library, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

• November 2014 in Shenzhen, China

• April 2016 in Kyoto, Japan

These meetings took place with generous help from the Wellcome Trust and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. They refined the idea of collecting and preserving original materials related to the HGP and laid out a clear strategy for a collaborative project.

The participants of this project come from the six countries that made up the HGP’s international consortium: the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Japan, and China.

As the 2003 announcement of the completion of the Human Genome Project recedes, it is critical to identify, archive, and organize these original materials before papers are shredded, e-mails are deleted, and memories of the major players fade.

This Catalog will be one site that will provide interactive links to all of the materials and collections and access to digital versions of materials when available, uniting information throughout the world into one virtual location and creating a comprehensive history of the Human Genome Project.

Six countries are participants of this project: UK, USA, France, Germany, Japan, and China.

About

Join us

Countries

International History of the Human Genome Project

CATALOG OF ORIGINAL MATERIALS

US-based HGP Institutions

Project Leaders: Mila Pollock, Jan Witkowski, Chris Donohue, Kris Wetterstrand

UNITED STATES

The idea to begin sequencing the entire human genome – the Human Genome Project (HGP) – originated in the United States in the mid-1980s. Scientists had begun to understand human beings at the molecular level years before. Molecular biology began in earnest with James Watson and Francis Crick’s elucidation of the structure of DNA in 1953. The scientific advances of the ensuing decades would make the idea of discerning all the base pairs in human DNA more of a possibility. These included the development of sequencing techniques by Frederick Sanger in the 1970s, and the automation of those methods by 1986.

It was in 1986 that researchers began to debate the feasibility of sequencing the entire genome. When scientists met that year for the annual Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Symposium, they held a rump session in which they argued back and forth about the potential cost and length of such a large project. Initially, many scientists were skeptical – either it would cost too much, take too long (or forever), or crowd out funding for other research.

Eventually, more biologists thought the benefits of sequencing the human genome far outweighed any concern about time or money. In 1988, the U.S. Congress provided initial funding for sequencing the human genome to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Department of Energy (DOE), and the NIH Office of Genome Research was established the following year. The publication of a joint research plan in 1990 marked the formal beginning of the Project.

The HGP was run jointly by the DOE and the NIH, which coordinated research among sequencing centers in Massachusetts, California, Missouri, Texas, Washington state, and New York. In 1989, the Office of Human Genome Research became the National Center for Human Genome Research (NCHGR), with James D. Watson as its first director. In 1997, the NCHGR became the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI).

In February 2001, the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium published 90% of the human genome sequence in Nature. The final and complete sequence was announced by the consortium in April 2003.

The Whitehead Institute/MIT Center for Genome Research, Cambridge, Mass., U.S.

Washington University School of Medicine Genome Sequencing Center, St. Louis, Mo., U.S.

United States DOE Joint Genome Institute, Walnut Creek, Calif., U.S.

Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Houston, Tex., U.S.

GTC Sequencing Center, Genome Therapeutics Corporation, Waltham, Mass., USA

Multimegabase Sequencing Center, The Institute for Systems Biology, Seattle, Wash.

Stanford Genome Technology Center, Stanford, Calif., U.S.

Stanford Human Genome Center and Department of Genetics, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, Calif., U.S.

University of Washington Genome Center, Seattle, Wash., U.S.

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Dallas, Tex., U.S.

University of Oklahoma's Advanced Center for Genome Technology, Dept. of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Norman, Okla., U.S.

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Lita Annenberg Hazen Genome Center, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y., U.S.

The Annotated & Interactive Scholarly Guide to the Project in the United States is a vast, online window into the Human Genome Project. It features a rich, meticulous gathering of resources, information, and links to original research, articles, videos, and many other materials. The scope spans not only the years bracketing the Project itself, but also the period leading to the launch and events following the Project’s completion. The guide contains a description of each resource, including contact and access information, as well as information about holdings and subject strengths of the resource. The Guide is published online as a wiki, with extensive use of internal links to cross reference events, people, events, and publications. The Guide is also available in an electronic book format and is supplied in Adobe PDF format.

In August 2012, the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) began a systematic effort to assimilate and organize historically relevant print and digital assets of the Institute. This effort has advanced past its pilot phase, with the vast majority of files housed at NHGRI now catalogued, digitized, and described. A number of other activities are also now underway. Significant scholarly work has also been produced on the history of genomics and the Human Genome Project.

Oral History Collection, Genome Research is the project of the CSHL Library and Archives organizes and records interviews with the critical particpants in the Human Genome Project and as well as investigators pursuing additional genome research. The interviews, which are presented as videos and as printed transcripts, cover a wide range of topics. Among those already interviewed are Francis Collins, James D. Watson, Michael Ashburner, Richard Gibbs, Eric Green, Maynard Olson, and J. Craig Venter.

Major contributors to the HGP were not restricted to scientists, funding bodies and companies. A key element at all stages were the meetings which brought scientists and administrators together to review research and discuss strategy. These included meetings held under the auspices of HUGO as well as specialist meetings like the Chromosome Mapping conferences and those held in Bermuda. But, arguably, the most important were the meetings at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory that began as the “Genome and Mapping” meetings in 1988 and became the “Biology of Genomes” meetings in 2004.

There were two principal reasons why these meetings became the meetings to attend. The first is that CSHL has a long history of holding meetings and many of the players in the HGP were already familiar these meetings. The second was that CSHL was the site of the famous session at the 51st where Paul Berg and Wally Gilbert initiated contentious discussion of the proposal to carry out the HGP.

The meetings have been the occasion for other events, most notably in 1998 when just before the meeting, Craig Venter declared that Celera would sequence the human genome and that the public effort should confine itself to the mouse. At the meeting itself, John Sulston and Michael Morgan announced that the Wellcome Trust intended to double its support of the public project.

The numbers show how much the community of HGP researchers valued the CSHL meetings. The 1988 meeting was attended by 203 participants presenting 96 abstracts. The number of participants rose rapidly to over 400 with 300 abstracts in 1992, to over 500 and 300 abstracts by 2000. In 2016 there were 532 participants and 345 abstracts.

The abstract books have a long history of having entertaining covers, many reflecting contemporary events. In this example taken from the 1991 abstract book, Jim Watson sells the HGP to Lee Hood, David Botstein, Sydney Brenner and Charles Cantor, while President George H. W. Bush looks on.

UK-based HGP Institutions

UNITED KINGDOM

The United Kingdom’s formal involvement in the Human Genome Project began in 1993, with the creation of the Sanger Centre (now known as the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute) – named after Frederick Sanger, two-time Nobel Laureate and the father of DNA sequencing. The Sanger Institute would end up making the largest single contribution to the Human Genome Project.

However, the origin of British genomics research went back to the previous decade. In the mid-1980s, Sydney Brenner was located at the prestigious Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB), at the University of Cambridge. In February 1986, he pushed for the creation of a small genome initiative at the LMB, which was funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC), a national organization that funds biomedical research in the United Kingdom.

The British government began funding the MRC’s genome research in 1989, pledging 11 million pounds sterling for the first three years.

Four years later, with the Sanger Institute established and the HGP underway in the United States, British researchers originally planned to complete one-sixth of the human genome sequence as part of the international consortium. The only U.K. institution involved in the genome project, the Sanger Institute scaled up its involvement in 1998. At the end of the HGP, in 2003, the U.K. had spent 150 million pounds sterling on the HGP and was ultimately responsible for completing over 30 percent of the final sequence.

That translates to more than 800 million base pairs of DNA. The Sanger Institute completed the sequences to chromosomes 1, 6, 9, 10, 13, 20, and 22, as well as the X chromosome. The sequencing work done by the Sanger Institute has led to the identification of genes correlated with diseases like leukemia, diabetes, Crohn’s disease, and glaucoma.

Wellcome Library is helping to safeguard the history of modern genomics by collecting the records of scientists and organisations involved in pioneering genomics research.

In January 2012 Wellcome Library began work on the UK strand of the HGAP, surveying the records of scientists and organisations in order to ensure that arrangements were put in place for their long-term preservation. This project focused on the years 1977-2004: from the development of Sanger sequencing to the publication of the “gold standard” human genome sequence. The survey work was completed in December 2013 and resulted in the addition of several new archives to the Library collections.

All of the genomics collections that were deposited in Wellcome Library as part of the HGAP have been catalogued and are available to researchers:

Michael Ashburner archive collection

Carol Churcher archive collection

Alan Coulson archive collection

Richard Durbin archive collection

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, The Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridgeshire, U. K.

Project Leaders: Jenny Shaw, Michael Morgan

FRANCE

Project Leader: Jean Weissenbach

France’s role in genomics has been significant. During the Human Genome Project, French researchers contributed to key developments in gene mapping and sequencing; they were also among the world leaders in finding genetic disease genes by positional cloning.

The epicenter of French genomic research was originally the Centre d’Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (now known as Fondation Jean Dausset-CEPH), located in the North of Paris. CEPH was created in 1984 from funds bequeathed to the Nobel Laureate Jean Dausset. The goal of CEPH was to collaborate with researchers around the world in producing a genetic linkage map. CEPH eventually began to collaborate with the French Muscular Dystrophy Association (AFM), and together Daniel Cohen (CEPH) and Bernard Barataud (AFM) created Genethon, the first and one of Europe’s largest genomics research centers.

After its founding in 1990, Genethon’s purpose was to coordinate genome mapping and sequencing and the mapping of disease genes. Researchers there were involved in three major genomics project: the effort to make a physical map of the genome (Daniel Cohen), a genetic linkage map (Jean Weissenbach), and an inventory of gene transcripts for muscle and nerve cells (Charles Auffray). Genethon produced a physical map of chromosome 21 in 1992 (Cohen, Chumakov).

One of the most important figures in French genome research was Jean Weissenbach, who made the first map of the Y chromosome in 1986. It was Weissenbach and his team at Genethon who produced the first linkage map of the human genome in 1992; later he would also be the leader of sequencing chromosome 14. Throughout the 1990s, Genethon continued to lead the way in identifying Mendelian disease genes.

Weissenbach would become the director of the French National Sequencing Center, known as Genoscope, which was created in the city of Evry in 1997 and would become a member of the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium.

German-based HGP Institutions

Department of Genome Analysis, Institute of Molecular Biotechnology, Jena, Germany

Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics, Berlin, Germany

GBF - German Research Centre for Biotechnology, Braunschweig, Germany

GERMANY

The German role in the Human Genome Project began in 1996, six years after the project had begun in the United States. Initially underfunded, the German portion of the genome project would soon become significant, with three institutions representing the country as members of the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium.

German researchers, led by Andre Rosenthal, Helmut Blöcker, and Hans Lehrach, eventually would be responsible for sequencing chromosomes 8 and 21, both completed in coordination with Japanese scientists.

The sequencing of chromosome 21 had started in the early 1990s. German and Japanese researchers began cooperating on the project in 1995. Ultimately, 170 scientists were involved from the Institute of Molecular Biology in Jena, the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics, and the German Research Centre for Biotechnology in Braunschweig; in Japan, the participating institutions were the RIKEN Genome Sciences Center and the Department of Molecular Biology at Keio University.

The sequence of chromosome 21 was completed in 2000, just before a May meeting on genome sequencing at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. It was only the second human chromosome to be fully sequenced.

It was after the completion of chromosome 21 that Rosenthal and other researchers surmised that biologists had overestimated the total number of human genes. For instance, scientists previously had thought they would find about 1,000 genes on chromosome 21; they ended up finding only a quarter of that.

As the HGP progressed, German officials, originally skeptical of the value of genomics research, began to devote more public funds to sequencing research. In the early 2000s, funding for the German Human Genome Project (DHGP) increased from approximately $21 million to approximately $32 million. Many German researchers didn’t think it was enough to catch up to the United States and other leaders in genomics. Nevertheless, Germany’s involvement in genomics research has only grown since then, beginning with the creation of the National Genome Research Network after the human genome sequence was completed.

Project Leader: Hans Lehrach

Late 70s, the Japanese scientist Akiyoshi Wada had an idea for developing an automatic DNA sequencing machine, a device that would eventually become critical for the success of the Human Genome Project. In 1981, under the support of STA (the Science and Technology Agency, Japan), Wada started a project for constructing an automated DNA sequencing machine. Under the stream of the project, Japanese scientists and engineers made several important contributions to DNA sequencing technologies, including the invention of four-color fluorescent dyes (by Yuzuru Fushimi) and multi-capillary array (by Hideki Kambara)

As formal human genome sequencing efforts crystallized in United States and the United Kingdom in the late 80’s, Ken-ichi Matsubara and his colleagues attempted to organize a Japanese Human Genome Project. This led to funding by the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports (Monbusho), the two-year pilot project from 1989 to 1990 and the five-year official project (700 million yen per year) from 1991 to1995. For promoting the project, the Center for the Huma Genome Analysis was launched at the Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo in 1991. Under the project, Japanese scientists contributed to building genetic and physical maps of the human genome, functional analysis of model organisms as well as technology and informatics development.

In 1996 at the meeting of the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium at Bermuda, the Japanese human genome project was allocated chromosome 21. Under the funding by STA, the Japanese team led by Yoshiyuki Sakaki and Nobuyoshi Shimizu, collaborating with the German team, played a key role in the successful sequencing of this chromosome, which was completed in May 2000 as the second completed human chromosome. In 1998, the RIKEN Genomic Sciences Center was established at Yokohama for expanding Japan’s role in the International Human Genome Project, and the RIKEN team led by Sakaki played a leading role in the completion of chromosome 11 and also made significant contribution to the completion of chromosome 18. Ultimately Japan contributed approximately 6% of the total human genome sequence. In addition, an international team led by RIKEN team successfully completed two chimpanzee chromosomes, chromosome 22 (corresponding to human chromosome 21) and chromosome Y. The RIKEN center also organized an international project called FANTOM for constructing a mouse cDNA encyclopedia. Japan has also made significant contribution to various international genome sequence projects such as Arabidopsis (24%), B.subtilis (31%) and so on.

Japan-based HGP Institutions

JAPAN

Department of Molecular Biology, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

RIKEN Genomic Sciences Center, Yokohama, Japan

Project Leader: Yoshi Sakaki

PROJECT LEADERS – USA

Ludmila (Mila) Pollock is the Executive Director of the Library & Archives at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, a position she has held since 1999. She has also been the leader of the Genentech Center for the History of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology since 2006. The CSHL Archives is internationally recognized for building extensive collections of original documents pertaining to the history of molecular biology and genetics. Under Mila Pollock's leadership, the CSHL Library & Archives has been awarded more than $2 million in grant support, and Mila has conceived and spearheaded numerous special projects, including the acclaimed CSHL Oral History Project: Talking Science, for which she interviewed more than 150 prominent international scientists in molecular biology, genetics, and biotechnology.

Pollock was one of the initiators of this project and is a member of the advisory committee. Her experience in helping to document the history of the HGP includes producing a comprehensive reference e-book on the subject, in collaboration with Kevin Davies and members of the CSHL Library & Archives staff.

Jan Witkowski is the former Executive Director of the Banbury Center at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and a Professor in the Watson School of Biological Sciences, the Laboratory’s graduate school. He obtained his B.Sc. in Zoology at the University of Southampton, UK, and his Ph.D. in biochemistry at the National Institute for Medical Research, London. He carried out postdoctoral research at the Royal Postgraduate Medical School, London, and at the Mayo Clinic, Minnesota, and the Imperial Cancer Research Fund, London. In 1986, he joined the Institute for Molecular Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, where he ran a laboratory performing DNA-based diagnosis of human genetic diseases.

Dr. Witkowski moved to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 1987. As director of the Banbury Center, he selected the topics for some 20 meetings each year. These covered molecular and cell biology; genetics; biotechnology; and societal issues of modern biology. Dr. Witkowski was also an editor on the Image Archive on the American Eugenics Movement and DNA from the Beginning projects.

His special interests are human molecular genetics, the interaction of science and society, and the history of modern experimental biology. He has published many papers on these topics and was a coauthor with Jim Watson, co-discoverer of the DNA double helix, of the second and third editions of Recombinant DNA. Most recently he was co-editor with Alex Gann of The Annotated and Illustrated Double Helix, a new edition of Watson's classic book The Double Helix. His latest book is The Road to Discovery: A Short History of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. He has edited and contributed to ten other books.

Dr. Witkowski is on the Faculty of the Watson School of Biological Sciences. He is a member of the Scientific Advisory Council of the James A. Baker Veterinary Research Institute (Cornell University) and former Editor-in-Chief of Trends in Biochemical Sciences.

Christopher Donohue is a historian in the History of Genomics Program at the National Human Genome Research Institute, which is part of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Donohue joined the project with a significant responsibility: to organize and process the original materials of the NHGRI, the leading genome institute in the United States.

Kris Wetterstrand is the Scientific Liaison to the Director for Extramural Activities at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI). From 1999 to 2010, in a different role within the Division of Extramural Research, she managed the institute’s grant portfolio during the final years of the Human Genome Project, as well as during the ENCODE Project and the Human Microbiome Project. From 2002 to 2009 she also served as Program Officer for the BAC Library Program at the National Institutes of Health. She holds an M.S. in genetics from Cornell University.

Wetterstrand is a recipient of the Department of Health and Human Services Secretary’s Award, which she won in 2001 for her work during the HGP.

PROJECT LEADERS – UK

Jenny Shaw is now Collections Development Manager at Wellcome Collection in London. She was originally hired by the Wellcome Library to lead the Human Genome Archive Project in the United Kingdom. With her help Wellcome added the following collections to their archives: Michael Ashburner, Carol Churcher, Ian Dunham, Richard Durbin, Matthew Jones and Sir John Sulston. She also organized the meeting Making the History of Post-War Life Sciences at the Wellcome Trust on Saturday 26 October 2013, which led to a Special Issue of Studies in History and Philosophy of the Biological and Biomedical Sciences on "Navigating 'big biology': challenges in historicizing and documenting the contemporary life sciences."

Michael Morgan Michael is a graduate of Trinity College, Dublin, and obtained his PhD (in Biochemistry) from Leicester University. He joined the Wellcome Trust in 1983 and prior to his retirement was director of Research Partnerships & Ventures and chief executive of the Wellcome Trust Genome Campus in Cambridge. He played a major role with Francis Collins and Ari Patrinos in the international coordination of the Human Genome Project from 1994 until his retirement from the Trust in 2002. He lead the Trust team that initiated and developed the Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, at Hinxton, including the Sanger Centre and the European Bioinformatics Institute. In 1996 he arranged the Bermuda meetings and was a major supporter of the Bermuda Principles of data release. During this period he lead the development of new enterprises such as DIAMOND, a new third generation synchrotron, a partnership with the UK government; the SNP Consortium (TSC), a partnership of the Trust and 12 private companies, and the Structural Genomics Consortium. All of these partnerships follow the Bermuda Principles and release their data into the public domain as early as possible and with no restrictions on their use.

Michael was Chief Scientific Officer of Genome Canada from 2006 to 2009 where he instituted a new consultative process to determine strategic priorities for Canadian government investments in genomic, proteomic, and allied research programmes. He retired in 2009.

PROJECT LEADERS – FRANCE

Jean Weissenbach is a renowned geneticist and the Director of Genoscope, or the French National Sequencing Center. After receiving his PhD, Weissenbach conducted post-doctoral research at the Weizmann Institute in Israel, and then further research at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. In 1982, he began working on human sex chromosomes, and in 1986 he made the first map of the Y chromosome. Weissenbach played an important role in the Human Genome Project: in 1992, he and his team produced the first linkage map of the genome.

Dr. Weissenbach participated in the first meeting for this project, held at the CSHL Banbury Center in 2009, and has been a leader in our efforts since then as a member of the advisory committee.

PROJECT LEADERS – GERMANY

Hans Lehrach is a professor at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin, Germany. He earned his PhD from MPI and was a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University, where he worked on RNA analysis and did pioneering work in cDNA cloning. He has also been group leader at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Heidelberg and head of the Genome Analysis Department at the Imperial Cancer Research Fund in London. His research has been integral to molecular genetics and genomics, including work on positional cloning, protein microarrays, and yeast artificial chromosomes. He took part in the Human Genome Project as well as the sequencing projects for the rat and Schizosaccharomyces Pombe genomes.

Dr. Lehrach joined this project to help document Germany’s role in the history of the HGP. He organized the 2016 meeting in Berlin, attended by major genome scientists in Germany as well as historians, librarians, and archivists.

PROJECT LEADERS – JAPAN

Dr. Yoshiyuki Sakaki is the former President of Toyohashi University of Technology in Toyohashi Japan, an emeritus professor of the University of Tokyo and an emeritus researcher of RIKEN. He obtained PhD at the University of Tokyo and then conducted research at the University of California, the Mitsubishi-kasei Institute of Life Sciences and Kyushu University. From late 80s, he has played integral roles in founding the Human Genome Project in Japan and organizing Japan’s role in the international consortium. Early 90s, he moved to the University of Tokyo and served as the director of the Center for the Human Genome Analysis at Institute of Medical Science (1991-95), and then the project director of RIKEN Genomic Sciences Center. The RIKEN team led by him made significant contribution to the completion of the human genome, particularly chromosome 21 and chromosome 11, and also the comparative study of human and primates through the completion of chimpanzee chromosome 22 and Y. He also promoted the human genome researches at global level as the President of HUGO (Human Genome Organization) from 2002 to 2005.

Dr. Sakaki was awarded the "Chevalier" from the French Government in 2001, in recognition of his contribution to the scientific cooperation between France and Japan, the Award of Japanese Society of Human Genetics (2001), the Chu-nichi Culture Award from the Chu-nichi Culture Foundation in 2003. He also obtained the Medal of Purple Ribbon (2003), a Person of Merit (2013) and the Order of the Sacred Treasure (2015) from the Japanese Government

PROJECT LEADERS – CHINA

Huanming Yang is the co-founder and Chairman of BGI-China. He and his partners have made a significant contribution to the international HGP, HapMap, and G1K projects, as well as many other animals, plants, and microorganisms, with many publications in Science, Nature, and other internationally prestigious journals.

Dr. Yang obtained his Ph.D. from the University of Copenhagen (Denmark) and postdoctoral trainings in France and USA. He was elected as an associate member of European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO) in 2006, an academician of Chinese Academy of Sciences in 2007, a fellow of TWAS in 2008, a foreign associate of National Academies of India in 2009, of Germany in 2012, of the USA in 2014 and of the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters in 2016.

China-based HGP Institutions

Beijing Genomics Institute/Human Genome Center, Institute of Genetics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

China’s participation in the Human Genome Project emerged through Jian Wang’s connections at the University of Washington in Seattle. Wang and Jun Yu had worked with Maynard Olsen who wanted more international participation in the HGP and welcomed the Chinese efforts to help. Wang and Yu recruited Huanming Yang, who was well connected to biologists in China. Along with Liu Siqi, Wang, Yu, and Yang founded the Beijing Genomics Institute in September 1999. The immediate aim was to produce DNA sequence for the HGP and they began to purchase automated sequencing machines for this purpose.

BGI began as a small adjunct to the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) Institute of Genetics. Gaining support within China for the sequencing efforts proved difficult. BGI’s founders argued that participation would provide access to advanced technologies and connections to a broad international network. Over the next four years, they raised almost $10 million from CAS, Yang’s hometown municipal government, and loans from employees, friends, and family. They also managed to secure a formal place in the HGP, ultimately sequencing 1% of human genome. BGI also managed to quickly buildup an extensive DNA sequencing capacity, by 2000 surpassing Germany and France and rivaling Japan. This work brought international recognition, followed by further recognition in China that allowed them to win further funds. In 2003, BGI played a central role in the sequencing of rice as part of the International Rice Genome Sequencing Consortium.

CHINA

International History of the Human Genome Project

c/o Mila Pollock: pollock@cshl.edu

Project Leader: Huanming (Henry) Yang

©2017 Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Library and Archives